Originally published in The WILD Magazine. ◊◊

French-born Anne-Lise Coste is a painterly poet and poetic painter whose text-based works are teasingly familiar and not completely legible. Her practice migrates in medium and motif, but there is something persistently introspective or perhaps autobiographical in Coste’s work; her paintings frequently turn to her own handwriting as both a subject and the vehicle for its communication. With some mischievousness, she agreed to meet for our interview in her downtown Manhattan studio at 8:30 in the morning, declining coffee but promising to bring her “morning humor.†Below is a conversation with the artist about ongoing ideas in her work and a new series of large format paintings she refers to as “haiku.â€

–

I’ve always wanted to ask—how much of your life’s work do you keep in this studio?

Do you mean from when I started tomake pieces? You know I immigrated here, so everything is in Europe with galleries. It’s in the storage of Zurich gallery, Gregor Staiger. Then it’s also in Stuttgart, in Amsterdam, Barcelona, and in Detroit, because I have a gallery there too—Susanne Hilberry. I think we already counted, there are like 4,000 works of mine. I want to beat Picasso. I think I read it in Wikipedia, [Picasso has] like 15,000 or something. At that time [reading that], I had already 2,000 or 3,000. So maybe I have already more than 4,000. I said if I live as long as he lived, I can do it.

You’ve been in this studio space for a year?

For one year, yes.

Do you ever find it hard to have your old work around while you’re working on new things?

A little bit, because I like the space more minimal. But really, if I can’t accept something, I can throw away. Everyone keeps saying “Don’t throw away! Never throw away!†[laughs] I threw away a lot of my work at art school and it’s true, I have some little regrets now. At the time I felt very uncomfortable with some of it—you judge it and you think it’s not very well done. I really set fire to it and burned everything. But I gave my mom the right to save things she liked, and now when I go back and look at them, it makes sense, and it’s great that she saved it. It’s good to have that possible reflection with what I was doing, and also to realize the invariants—what didn’t change and what was already there.

You also rework old canvases. Do you feel that same sense of loss when you paint over or paint on the backside of a work you already made? Maybe it’s not the same kind of loss you have in throwing something away, because you still have the original object.

No, most of the time when I rework, I’m agreeing with the work. For instance this one. [points to a canvas] In this work, the first layer was tempera in 2010. Then came the spray paint this year. And then yesterday, I did this black drawing of a kid. It looks so much like a kid—like a baby.

You go between text and imagery, and I haven’t found the right word to refer to your images. Maybe you could tell me how to describe what you do?

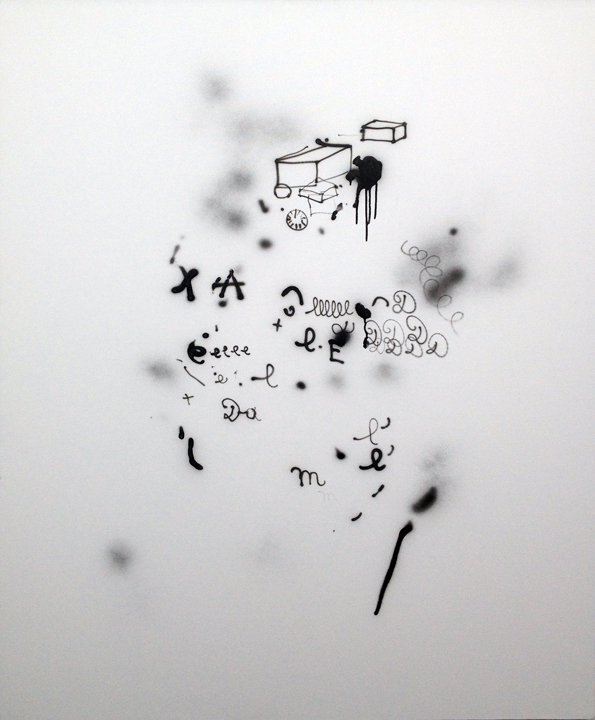

I remember that I was used to saying “Text becomes an image, and image becomes a text.†You know? I don’t know if it’s a confusion, but it’s all mixed like that. You can look at it just look at it as text, or just shapes on your eyes. It’s the beginning of letters that could look like shapes. And it’s undefined, or unfinished. It’s very open to the reading.

Your new painting series, you called the works haiku—can you explain again why you call them that?

Oh, they’re very minimal forms, and very open to interpretation. And on the other [hand], they’re very straight. I think that when you read a haiku, it is direct, straight to the point. I like that. You can embrace immediately the image. And on the other side, you look more and more, you can start to travel around inside and it’s way more open than the first gaze.

When you apply titles to your works, how do you feel about adding a different layer of text onto your already textual work?

Usually the title I try to pick is what’s happening in the canvas. Like this one, for instance, I believe I’m going to call it “m, A, three cubes—†oh wait, this one is not, [laughs] so two, “m, A, two cubes.â€

You’ve looked at so many different ways of writing and painting. Is there one that you find more comfortable than the others?

Actually, to have come back to airbrush I feel very good. Because it has, I told you last time, the urgency I have in doing art. Each time I enter here, there is no real preparation except setting up the [airbrush] gun and water. It’s so direct and, bon. Now I’m restraining myself with using only black. But I can show you, I bought colors yesterday. I think this week until I leave for France, I will be colorful.

You’re done with black?

No, no. Done with black? Not for life. I think I want to do some more haiku these days in fluorescent.

You went for neon and metallic.

Yes. They are beautiful.

So how does this compare to spray painting in your last series?

It smells much less. It’s much less corrosive and intoxicating and it’s way more flexible. I think you have way more control. I can change the nozzle, but I don’t know if I’ll get into that. I can get both [thick] and [thin]. There is a range of apparitions. I think it’s very airy.

I think it’s very fitting for the haiku.

Yes. I don’t know if I told you, but my friend Alina Bliumis is an artist. She gave me the best adjective for the show I did at Helen’s gallery, [toomer labzda]. She said she loved the way the work was presented and [told me], “Your show was windy.†Exactly! You know I told you I worked at the window, and I worked with the wind. She felt it, and it’s a big compliment. If I can reach this status in art with my art—that it flies, that goes with the wind—it’s a big compliment.

And Alina was one of the first to see the airbrushes, and she said “Your studio is not that clean, how do you keep such a whiteness?†It’s true, it has something immaculate. The canvas itself becomes a surface to look at, to feel, and appreciate. Yes!

So my first teacher in oil painting told me that I was never supposed to use pure black or pure white in a work because it kills the painting. She was a believer of the Venetian school colorists, and we painted with burnt umber and nickel yellow instead of black and white. I heard that with each painting teacher I had. Were you ever told that?

I’ve never heard that! But what I can say about the minimalism of my paintings is that I wanted to touch [the canvas] less. In art school my first year, I was painting squares and I was very attracted to the minimalists. I was buying raw canvases and not priming them, because that would already be too much. I would, with the help of tape, create a square—no rulers, no measurements, just a square as it feels like a square—and then I would paint inside. At the time, and I hope I am still, I was very concerned with the environment, so I was buying organic pigments. I did a white square, a blue square, and a green square. And the teacher told me “This is not painting. This is tainting.†[laughs] I mean, we were in 1995, so contemporary art did exist. Painting can be tainting! So they could have said “Oh you’re interested in not touching too much, not about the brush or brushstroke. Go see these artists!†Anyway, no. They were very angry at it. But me, I couldn’t understand because they were extremely peaceful and meditative, floating. These works [now], I think, have a dialogue with those squares.

I remember a conversation I had with Helen Toomer, where she said that she could tell the differences in your mood based on looking at the pieces. Does your mood reflect in your works?

Yes. It could be that I work every day and one piece is from the morning around 10, and the other one around 3pm. So there is a map of feelings and emotions definitely. I think it’s more visible because I come here without a project. The only thing I know is that there will be a canvas on the wall and I will be facing it with my gun. So that’s why I think you see it more. Unlike if I said “Ok, on the first of September, I will do a pink sculpture of that size of that material.†Then you see less of the mood because you have to go buy the material, maybe you have to wait on that material, and certainly you might have designed the thing. Maybe that’s why there’s less of a reflection of change in mood, because it’s already premeditated. And me, I am wanting to avoid any premeditation, any sense of planning. It’s really to let it go. I don’t know about the haiku and how spontaneous they are, but I feel it’s another connection I have with them. That the balance comes by itself. You are so concentrated that it builds by itself. I would say that the unbalanced becomes balanced.

I had one last question. In the two press releases I’ve seen from your solo shows, and the readings that you’ve done, you’ve used poetry instead of necessarily explaining your practice. Is there a reason you use a second layer of abstraction?Â

[laughs] I want to go back to a story, the first time I had seen art. For me, it was a piece by [Joan] Miró, perhaps you have it in mind and I already told you that story, but that piece was a piece of paper that was stained—literally a stain of blue—and he wrote with his handwriting on the paper in Spanish, “blue, the color of my dreams.†And being in front of such an art piece—me!—not having knowledge of art at all because of my social class and where I was born, I saw that art could be a little piece of paper, meaning it’s not a canvas, it can be accessible. Anne-Lise Coste at thirteen years old, I can take a piece of paper! It’s a stain, it doesn’t require knowledge in drawing, it’s not a naked woman or architecture. And then you can write on the art piece something poetic. And you say “my†also. The artwork talking about itself, so it’s not just the poésie or big notions or goodness—do you say goodness?—or anything like that. It’s about an artist who writes about himself in a very subjective way, so that impressed me. And I hope that answered your question about poésie —it’s a prolongation.

Images courtesy of the artist.